I still remember the phone call like it was yesterday. As I was preparing to leave for the university on a warm September morning in 2015, I received an unexpected call from my mother. In a very emotional conversation, she shared the devastating news that she had decided to divorce my father after almost 40 years of marriage and there was nothing I could say or do to stop her. I hung up the phone, feeling shocked and confused. What added to my agony was that I was in my second month of teaching as an assistant professor in human development and family sciences and was scheduled to teach 38 undergraduates that day. How on earth was I supposed to teach about families, when my own family of origin was falling apart?

As the sadness of this phone call washed over me, I relayed the news to my wife, and then said goodbye to her and our four children as I left for work. Although I did not tell my children about my parents’ separation until days later, they could sense that something was amiss. It took great courage that day to put on a brave face, lecture for three hours, and later meet with students. In fact, the fallout from my parents’ divorce felt like a cloud hanging over me for the next year. I would not have made it through this difficult time without the extensive training and education I have received as a marriage and family therapist, a reliance on my faith, and the continual support from my wife.

I love my parents, and in no way is this blog post meant to disparage them, but in sharing my story and the suffering of having my family ripped apart, I hope to bring some help to others. I have learned and grown a lot from my parents’ divorce. The experience has motivated me in my research and in my teaching about couples and families. As a therapist and as a professor, it has also deepened my empathy and understanding of the pain my clients often suffer, as well as the experiences of my students who are also children of divorce. And, of course, it has empowered my wife and I to reevaluate our relationship and to find ways to strengthen and protect it. More than ever, we want to provide a loving and committed example to our children and to be strong link in the chain of generations. One of the often-unspoken symptoms that can accompany parental divorce is that relationships suddenly feel more fragile.

One of the ways I responded to my parents’ divorce in the classroom was by talking about my own story and encouraging my students to share theirs. One of my students shared the following during an in-class assignment, and she gave me permission to share it here:

“My parents divorced when I was 15. It was the hardest time of my life. To me and my sister, this divorce was very surprising to us. My Mom and Dad did a very good job at hiding their problems from us as we were growing up…After my parents got divorced and when I was older, I found out the true reason that my parents got divorced. My dad had an affair, went to alcohol and drugs, and there was just no relationship between them anymore. I really think this affected me and my sister more than if we would have been abused or neglected. There are certain things that always bring back painful memories…These are things that will be with me for the rest of my life. I think if couples were more committed to each other families would have a different dynamic. After my parents’ divorce, my relationship with my Mom and Dad has not been the same. If my parents had been more committed to each other, then I would not have gone through what I did. I wouldn’t have seen my house destroyed after my Mom asked for a divorce. I wouldn’t have come home to my Dad being arrested because of his anger. I wouldn’t have to be separated from my Dad because of a restraining order. I wouldn’t have all of these painful memories if only my parents would have been more committed.”

There are millions of children both young and old with unique stories to share regarding parental divorce. A recently published book that was discussed at the Institute for Family Studies is one powerful resource for learning about how adults were personally impacted by their parents’ divorce. I believe it can be therapeutic for children and adults who have experienced parental divorce to have a way to share their stories. For some children of divorce, writing can be helpful, and for others, music can be a powerful outlet (see here and here). Although parental divorce can be a life-altering trial and for children and adults, leading experts in child development have consistently indicated that healing is possible, although it can take great effort on the part of the child and those that support them. In her 2017 book Strengthening Family Resilience, Froma Walsh one of the leading scholars on this issue, has noted that individual resilience is most likely to be achieved by an increase in self-esteem, self-efficacy, and having an internal locus of control (see Rutter, 1987).

Resilient Commitment

Much of the research literature indicates that divorce can have a substantially negative impact on both children and adults (Amato, 2010), and become more likely in future generations (Amato & Patterson, 2017). Some experts have even raised questions over whether a “good divorce” actually exists (Amato, Kane, & James, 2011) except in cases of significant conflict and/or abuse. While we may be finally seeing a decrease in gray divorce, I think the mistaken assumption often made by parents in their 50s, 60s, and 70s is now that their children are grown and have left the nest, divorce simply won’t be as hurtful or disruptive. Having experienced this myself, I would encourage older couples considering divorce to slow down, seek therapy, and consider the long-term consequences to their children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren. The greatest gift parents can give to their children and their grandchildren is a loving and committed marriage.

As reported by Paul Amato and Sarah Patterson in a recent study, the intergenerational transmission of divorce “appears to be a real phenomenon—perhaps as well established as any finding in the social sciences… marital instability in the family of origin continues to be one of the most reliable predictors of adult divorce” (Amato & Patterson, 2017, p. 723).

That being said, I believe there is hope for adults who have experienced parental divorce or family instability, as I have found in my research. I feel strongly that one of the underreported stories about divorce and family instability is that children of divorce are not destined to repeat the cycle of divorce if they actively decide as a couple to be committed. Sure, the odds may be more stacked against them, but if we believe that couples can exercise their personal agency, then there are reasons to believe that couples can choose to be different.

In a research study I conducted several years ago (Sibley et al., 2015), I interviewed 15 newly married couples (30 participants) who each had been married approximately 13 months. At the time the data was collected 10 of the 30 participants had experienced parental divorce. I asked each newlywed questions about their personal definitions and beliefs about commitment, where they had learned these ideas, and how they were communicating commitment in their own marriage. I was stunned by what I learned: all 30 participants indicated that negative examples of commitment (parental divorce, infidelity, conflict, etc.) had taught them what not to do in relationships. For these couples, the negative examples of commitment were observed from many different sources, such as their parents, siblings, friends, and extended family members. These newlyweds expressed that the negative examples were empowering for them as they had made the transition to marriage. As one participant explained (Sibley et al., 2015):

“Their divorce totally made me a better person. Better son, eventually a better father, a better husband… it’s not all rainbows and butterflies. If you want to be committed to marriage you have to constantly work at it and it won’t always be easy once you say I do and come home from the honeymoon…Because of my parents’ divorce I realize you can’t just coast…So, I think that there’s a lot of ways it affected me, but as far as commitment it affected me a lot. It opened my eyes to work that needs to be put into it” (p. 12).

This research study led to the development of a theory I call “resilient commitment,” which I have continued researching and writing about (this manuscript provides a more extensive overview of the theory). Resilient commitment is a new way of thinking about individuals who still believe in the sustainability and viability of romantic relationships, even after experiencing parental divorce or family instability. Someone who is demonstrating resilient commitment has made meaning from both the positive and negative examples of commitment they have observed and believe that they can obtain and sustain their own relationships.

On a personal note, my wife and I both come from divorced homes, but we are striving to have a vibrant and healthy marriage. Although I don’t have data to back this up, I believe that there are thousands upon thousands of couples, like us, that choose to have healthier relationships than they experienced in their own families of origin. To begin investigating the theory of resilient commitment at a larger scale, I surveyed several thousand emerging adults (18-29 years old) about their beliefs about commitment, and how their parents’ and the examples of others have shaped their attitudes about romantic relationships and their ability to succeed in them.

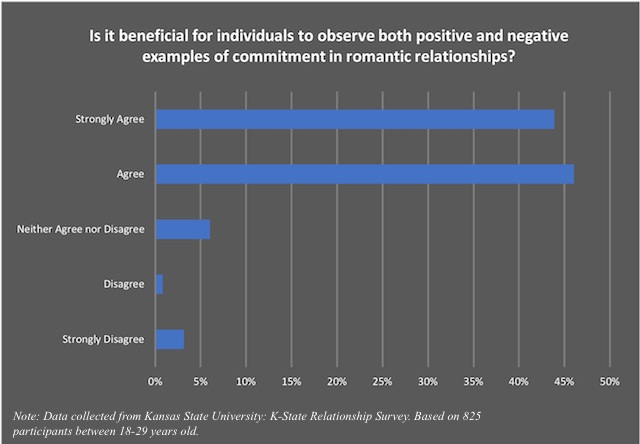

I conducted a preliminary examination of this theory, using a sample of 825 emerging adults, where I defined negative and positive examples of commitment and asked participants several questions. As you can see from the figure below, the majority indicated that it was beneficial to observe both positive and negative examples. Interestingly, the majority of these participants also reported that positive and negative examples of commitment are both of equal value in order to develop an understanding and knowledge of what it means to be committed to someone.

As I’ve explored the data I have been collecting with emerging adults, one constant theme has emerged: they are learning daily what to do and what not to do in romantic relationships from the examples they observe. Many of the participants seem to understand what they should be doing in relationships to find stability and satisfaction, but struggle to put these solutions into practice and to avoid repeating the negative examples they have observed.

Consistent with other research studies (e.g., Cui, Fincham, & Durtschi, 2011), I have found that parental figures are still the main source of information about marriage, divorce, and relationships. However, social media and technology are having a profound impact on younger generations and the how the form and maintain romantic relationships. As one relationship scholar has observed, “in the age of ambiguity, cuelessness abounds in dating and mating” and it has become ever more unclear how to find the path that leads to marriage. The ambiguity and uncertainty in relationships is unfortunate, because the majority of emerging adults continue to indicate that marriage remains a lifetime goal (e.g., Willoughby & James, 2017). Perhaps one of the ways we can encourage marriage and healthy relationships is by providing relationship education that focuses on important protective factors such as commitment, sacrifice and forgiveness (Fincham, Stanley, & Beach, 2007).

As cohabitation increases and family instability continues to rise, we would do well to find ways to encourage adolescents and emerging adults to be wise and intentional in their romantic decision-making. After all, most millennials seem to be looking for parental guidance on love. One of the ways that we can start is by carefully considering how our own examples are impacting future generations. My wife and I find healing and purpose in knowing that we can be resilient in choosing to be committed to each other, and we hope to transmit that marital resilience to our children and someday our grandchildren.

*This article was first posted at the blog for The Institute for Family Studies on March 20, 2018.

References

- Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 3, 650-666.

- Amato, P. R., Kane, J. B., & James, S. (2011). Reconsidering the “good divorce”. Family Relations, 60, 5, 511-524.

- Amato, P. R., & Patterson, S. (2017). The intergenerational transmission of union instability in early adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 79, 3, 723-738.

- Cui, M., Fincham, F.D, & Durtschi, J. A. (2011). The effect of parental divorce on young adults’ romantic relationship dissolution: What makes a difference?. Personal Relationships, 18(3), 410-426.

- Fincham, F. D., Stanley, S. M., & Beach, S. R. H. (2007). Transformative processes in marriage: An analysis of emerging trends. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 275 – 292.

- Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57, 3, 316-331.

- Sibley, D. S. (2015). Exploring the theory of resilient commitment in emerging adulthood: A qualitative inquiry. Doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/18950/

- Sibley, D. S., Springer, P. R., Vennum, A., & Hollist, C. S. (2015). An exploration of the construction of commitment leading to marriage. Marriage & Family Review, 51, 2, 183-203.

- Walsh, F. (2017). Strengthening family resilience. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Willoughby, B. J., & James, S. L. (2017). The marriage paradox: Why emerging adults love marriage yet push it aside. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Discover more from Decide To Commit

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.